Nellie Bly: Around the World

On Nov. 14, 1889, New York World reporter and Western Pa. native Nellie Bly started a 25,000-mile journey around the world, inspired by the popular Jules Verne book “Around the World in Eighty Days.”

Nearly 131 years later, we’re sharing her adventures in real time. Follow her thrilling journey around the globe here now through January 2021.

Note to Readers: The language and terminology used in these historical materials reflects the context and culture of the creator, Nellie Bly, and may include stereotypes in words, phrases, and attitudes that were wrong then and are wrong now. Rather than remove this content, we want to acknowledge its harmful impact, learn from it, and spark conversation to create a more inclusive future together.

CONTENT RESEARCHED AND WRITTEN BY LAWSON PACE, HISTORY CENTER INTERN

Nellie Bly: Around the World in 72 Days

- Meet Nellie Bly

- DAY 1 – NOV. 14, 1889: The Race Begins

- Day 3 – Nov. 16, 1889: A Competitor Joins the Race

- Day 6 – Nov. 19, 1889: Luxury at Sea

- Day 9 – Nov. 22, 1889: A Visit with Jules Verne

- Day 14 – Nov. 27, 1889: The British Empire

- Day 20 – Dec. 3, 1889: The Port of Aden

- Day 25 – Dec. 8, 1889: Comfortable in Colombo

- Day 28 – Dec. 11, 1889: Searching for Ceylon

- Day 33 – Dec. 16, 1889: At Penang

- Day 35 – Dec. 18, 1889: A New Companion

- Day 40 – Dec. 23, 1889: Hong Kong- The Crown Colony

- Day 42 – Dec. 25, 1889: Christmas in Canton

- Day 50 – Jan. 2, 1890: The New Year Begins

- Day 53 – Jan. 5, 1890: Japan: A Nation Transformed

- Day 58 – Jan. 10, 1890: Life in Steerage

- Day 64 – Jan. 16, 1890: Racing Against Time

- Day 70 – Jan. 22, 1890: Homeward Bound

- Day 73 – Jan. 25, 1890: The Journey Completed

- Nellie Bly: A Postscript

Meet Nellie Bly

Born on May 5, 1864 in the small town of Cochran’s Mills, about 30 miles northeast of Pittsburgh, Elizabeth Jane Cochran grew up in nearby Apollo. At the age of 15, she began to take classes at Indiana Normal School (now Indiana University of Pennsylvania), but dropped out that same year because her family could not afford the costs. Since her mother and stepfather had divorced, Cochran moved to Pittsburgh in 1880 to be closer to her two older brothers. She and her mother struggled to get by. In January 1885, while living in Allegheny City (now Pittsburgh’s North Side), Cochran wrote a letter to the editor of the Pittsburgh Dispatch, George Madden, in response to a column that argued for a traditional role for women in society. Madden, intrigued by her unique voice, asked her to write an article for his newspaper. Impressed with what she sent him, he hired her as a reporter for the Dispatch at five dollars per week. There she acquired the pen name (taken from a song by Pittsburgher Stephen Foster) that she has been known by ever since: Nellie Bly.

Nellie Bly pictured seated in Mexico, 1886. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

As a young reporter at the Dispatch, Bly mostly wrote about fashion, the home, and women’s issues, as was expected for female journalists at the time. However, she grew bored with day-to-day newspaper life and took an assignment to go to Mexico. Only 21 years old, Bly travelled with her mother across the southern border into Mexico. She spent six months there, sending reports home about the government and culture. Eventually, fearing that she would be arrested for criticizing the government, she cut her stay short and returned home. Though glad to be home, Nellie’s adventurous spirit could not last another year at the Dispatch. In March 1887, someone on the newspaper staff found a note from Bly that confidently declared, “I am off for New York. Look for me.”

A drawing of the Pittsburgh Dispatch Building, which stood on Fifth Avenue near Duquesne University, 1876. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

In New York, Bly got a job writing for the New York World, a major Democratic newspaper rising under the leadership of Joseph Pulitzer. While there, she pretended to have a mental illness so she would be admitted to the Women’s Asylum on Blackwell Island. After staying there for 10 days, she was released. She went on to write a best-selling report on the terrible conditions within the hospital, “Ten Days in a Mad-House.” Bly’s daring feat of undercover investigative journalism began the tradition of the so-called “stunt girls,” female journalists sent to report on stories, often about social injustice, that were shocking or amazing in some way. This was a reversal of the traditional roles that women filled in journalism, and newspapers competed fiercely to see who could offer the more astounding story. The biggest idea yet came to Bly one night in 1888. She brought the idea to her editor the following day: what if she were to travel around the world? If she could do it in less than 80 days, she would improve upon the fictional adventure of Phileas Fogg, the main character in Jules Verne’s “Around the World in Eighty Days.” Her editor was skeptical. He pointed out that she could only speak English, would have to be escorted by a man, and (being a woman) would obviously pack too much luggage to make good time. He even suggested sending a man on the trip instead. She angrily declared, “Start the man, and I’ll start the same day for some other newspaper and beat him.” However, it would take a full year, until a fateful November day in 1889, for Nellie’s idea to come to fruition.

The cover of the first edition of Nellie Bly’s “Ten Days in a Mad-House,” which helped to launch a new era in investigative journalism, 1887. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Day 1 – Nov. 14, 1889: The Race Begins

Many adventurers considered travelling around the world trying to beat the record of Phileas Fogg, the fictional hero of Jules Verne’s book Around the World in 80 Days. In the year after Nellie Bly brought the idea to her editor, other people openly discussed the race against time, including another writer at The World. Showman Henry C. Jarrett’s announcement that he would be making the trip finally inspired Bly’s editor to send her. For Bly, however, the call she received on the chilly Tuesday evening of November 12, 1889 came as a total surprise. Her editor wanted her to leave in the next couple of days on a trip around the world. Nellie Bly, never one to back down from a challenge, said yes.

Nellie Bly posing for a publicity shot for The World, wearing her travelling gown and holding her handbag, Feb. 21, 1890. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Rather than setting off the following morning on the speedy City of Paris, Bly chose to travel on the German ocean liner SS Augusta Victoria so she had an extra day to prepare. On her last full day in New York she visited Ghormley’s, a dressmaker on Fifth Avenue, who made her iconic travelling gown. She also bought the satchel that she would carry around the world. Just seven inches tall and 16 inches wide, its size represented Bly’s commitment to independence and self-reliance. Many people in Bly’s time believed that a woman would require many suitcases for such a journey, making it impossible to travel quickly or alone. It seemed to please Bly to surprise people; when asked by a reporter if she needed help with her luggage, she responded with what might have been amusement, saying, “My luggage is already aboard, thank you. I brought it on myself.” Bly was able to fit a surprising amount in such a small bag. According to her account, she packed:

…two traveling caps, three veils, a pair of slippers, a complete outfit of toilet articles, ink-stand, pens, pencils, and copy-paper, pins, needles and thread, a dressing gown, a tennis blazer, a small flask and a drinking cup, several complete changes of underwear, a liberal supply of handkerchiefs and fresh ruchings and most bulky and uncompromising of all, a jar of cold cream to keep my face from chapping in the varied climates I should encounter.

In addition to this small piece of luggage and the clothes that she wore, Bly brought British and American money given to her by The World along with a pair of earrings, two bracelets, and a gold thumb ring that she wore as a good-luck charm. She had worn it the day she was hired at The World, and in the days since, “the only three days that it has been absent from my finger, I have had bad luck.” She may have needed the luck. She had never been at sea, only spoke English, and had recently suffered from severe headaches. Completing the journey in the hoped-for 75 days would be very difficult, and the trip would also be dangerous. Bly wrote her will before her departure and sent it to her mother. Nevertheless, she told reporters, “I have no qualms of fear.” At 9:40 on the morning of Thursday, November 14, 1889, the Augusta Victoria left the docks at Hoboken, New Jersey, travelled down the Hudson River, passed through the Narrows, and steamed out into the Atlantic Ocean. Nellie Bly had set off on her quest around the world!

British Sovereign gold coin, worth £1, minted 1878. The World gave Bly £200 of British coins and notes, along with an unspecified amount of American money. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Day 3 – Nov. 16, 1889: A Competitor Joins the Race

Photograph of Elizabeth Bisland dressed as she would have been on her travels.

Though she was unaware of it at the time, Nellie Bly’s journey quickly attracted interest from other newspapers and journals. John Brisben Walker, owner of Cosmopolitan magazine, became intrigued by the news that Bly planned to beat the fictional record set in Jules Verne’s 1872 novel “Around the World in Eighty Days.” Walker knew that if he could take advantage of the already popular story, he might make the Cosmopolitan, a relatively new publication, famous. Shortly after the Augusta Victoria steamed out of New York Harbor on November 14th, Walker sent a message to one of his promising young editors, Elizabeth Bisland, asking her to come to the office. Only 28 years old, she was about to race Nellie Bly around the world.

Photograph of Elizabeth Bisland, c. 1891.

Like her eventual rival Nellie Bly, Bisland had been born far from the city where she would eventually make a name for herself. Her father was a prosperous Louisiana planter who served as a quartermaster and surgeon in the Confederate army until captured at Vicksburg. After the war’s end, when the family returned to their plantation on Bayou Teche, they found it in ruins. Unable to keep up their payments, the Bislands ceded the property to its previous owner, a planter who had remained loyal to the Union. Bisland eventually sought employment to support her struggling family. Unlike Bly, she had an effortlessly elegant writing style; Bisland had begun her career publishing her poetry in local newspapers. She eventually became an editor at the New Orleans Times-Democrat but dreamed of bigger and better opportunities. Bisland came to New York and found work at Cosmopolitan magazine, where she served as t he editor for the literary section.

When Bisland arrived at the offices of the Cosmopolitan on Nov. 14, Walker asked if she would be willing to make a trip around the world competing with Nellie Bly. Bisland originally thought he might be joking. It took an hour-long argument to convince her to go. Almost noon by the time she agreed, Bisland had only hours to prepare for the journey. The afternoon raced by, a blur of preparations. Bisland later wrote that she found herself “practically stupefied with astonishment.” Walker decided that Bisland would have a better chance of beating Bly if she traveled west instead of east. She left that day at 6:00 pm, headed for Chicago. For the next few weeks, the newspapers of America would be filled with stories about the race between the two brave journalists circling the globe. Everyone wondered who would reach New York first, Nellie Bly or Elizabeth Bisland?

Day 6 – Nov. 19, 1889: Luxury at Sea

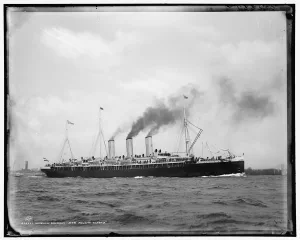

Photograph of the Augusta Victoria, c. 1890. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

As Nellie Bly’s ship steamed away from land, she began to worry about her journey. Despite the brave face she put on for reporters, friends, and family, she could see many potential dangers ahead. Her first challenge would be to adjust to life at sea. Although Nellie knew that she would visit many exotic and interesting places on her trip, she also knew that a lot of her time would be spent traveling on ocean liners. Though seasick for most of her first day on board, after she recovered, she had a full week to experience life on one of the finest ocean liners in the world.

The Augusta Victoria, a German vessel operated by the Hamburg-America Line, was practically brand new, having crossed the Atlantic for the first time in May 1889. She broke the record for the fastest westbound Atlantic crossing on that voyage, racing to New York in only seven days. Though not the largest transatlantic ocean liner, at nearly 500 feet long, she was certainly one of the most luxurious. The ship had the most magnificent interior design available at the time, with a beautiful dining room, an ornate atrium with many statues, and a “gothic smoking room.” Reading, playing cards, and smoking cigars were all common pastimes on board. The highlight of each day was dinner, when guests would gather for a formal meal. A menu from 1893 (bottom right) offers barley soup, salad, fish, roast beef, a fruit dessert called compote, and a German pastry called Schneebälle (Snowball). Passengers were also serenaded by piano during and after the meal.

During her time on the Augusta Victoria, Bly got to know her travelling companions, including the ship’s captain, Adolph Albers. Despite their eccentricities, she came to like them. She later wrote, “I had not known one of the passengers when I left New York seven days before, but I realized, now that I was so soon to separate from them, that I regretted the parting very much.” Whatever her feelings, there would be no delay. The world awaited Nellie Bly.

A menu from the Augusta Victoria, Aug. 1893. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

The dining room on the Augusta Victoria depicted on a menu, Jan. 1900. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

Day 9 – Nov. 22, 1889: A Visit with Jules Verne

The Houses of Parliament as Nellie Bly saw them on her way to the London offices of The World, c. 1890s. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

At 2:30 am on Sunday morning, Nellie Bly stepped off the SS Augusta Victoria into the darkness. After spending nearly eight days crossing the stormy Atlantic, she now began the leg of her journey that may have been more hectic than any other. The London correspondent for the New York World told her that he had received a letter from Jules Verne, author of “Around the World in Eighty Days,” inviting Bly to visit his wife and him at their home. Bly jumped at the chance. The correspondent warned her that to visit Verne without losing all-important time, she would have to be moving for the next 24 hours. She responded that she would not “think about sleep or rest.”

A tugboat took Bly from the place where she had disembarked in the English Channel to the run-down docks of Southampton. From there, she took a special mail train to London. London was a blur; she traveled from Waterloo Station to the London offices of The World, and from there to the American legation on Victoria Street in Westminster. She ate breakfast at Charing Cross Station before leaving and heading east. Finding British trains to be much slower than those in America, Bly slept through the journey of several hours to Folkestone, in the extreme southeast of England. At that point, she took a ferry across the Channel to Boulogne—a journey of only about 30 miles! There she took her first major detour, traveling about 65 miles south to the city of Amiens.

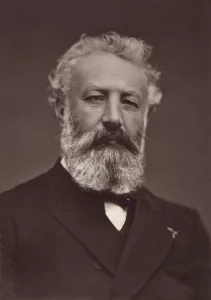

Print of Jules Verne, 1884. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

When she arrived at the station in Amiens, a city of almost 80,000 people, Nellie Bly was understandably nervous. Jules Verne was not only the inspiration for her journey but also one of the most renowned authors of his time. He wrote world-famous novels such as “Journey to the Center of the Earth,” “Twenty-Thousand Leagues Under the Sea,” and, of course, “Around the World in Eighty Days, “published in 1873. “Around the World” told the story of a British aristocrat named Phileas Fogg who wagered £20,000 (worth over £2,000,000 today) that he could travel all the way around the globe in 80 days. The novel was full of swashbuckling adventure: Fogg was pursued by a detective, rode an elephant across India, was attacked by Native Americans, and ultimately made it back to London with only hours to spare. Although this thrilling story made “Around the World” a smash hit in Britain and America, Bly probably hoped to avoid this kind of adventure on her own journey.

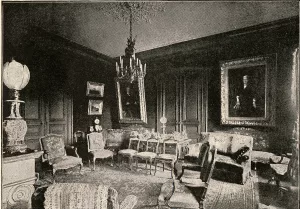

She also had to cope with the fact that neither of them spoke more than a few words of the other’s language. Nevertheless, Verne made a very positive impression on Bly. A rather short man, he had kind eyes, a full beard, and white hair “standing up in artistic disorder.” The two traveled together to the gates of the Verne House where they were greeted by the Vernes’ dog. They conversed through a translator in Verne’s grand salon. Verne, interested in the route that Bly planned to take, asked why she did not plan on crossing India by rail like his character Phileas Fogg. She responded that she would save time going by sea. They plotted out their contrasting journeys on a large map. Nellie also asked to see his study, which she found surprisingly small, and his library, which she thought was enormous. Although enjoying herself, Bly knew that she had to leave. A single missed connection could cost her the record. Saying her farewells to the Vernes, she stepped back out into the cold and windy November evening, headed to Calais. At about 1:30 in the morning, she boarded the mail train bound for Italy. After 24 hours, Nellie Bly could finally rest.

Jules Verne’s grand salon in his house in Amiens, 1894. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Exterior view of Jules Verne’s house in Amiens, 1894. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Day 14 – Nov. 27, 1889: The British Empire

Map of the British Empire, 1889. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

As the steamship Victoria approached the coast of Egypt on the afternoon of November 27, Nellie Bly’s journey began to change. She entered the part of the world referred to in the U.S. and Western Europe as “the East” or “the Orient,” the place where she would spend most of her journey. Many people at that time believed that there was a difference between the so-called “civilized” world of the West and the “exotic” world of the East. Though she would see many things that were unfamiliar and spectacular in the coming days of her journey, Bly was not travelling through a completely foreign land: every port that she would visit from Egypt to China was a part of the British Empire.

By 1889, the colonial possessions of the United Kingdom spanned six continents — it was said that the sun never set on the empire. The breadth of this worldwide empire meant that, for better or for worse, the world was smaller than it had ever been. In fact, this increase in the speed of travel and communication inspired Jules Verne’s novel Around the World in Eighty Days, which itself inspired Nellie Bly’s journey. No location on her trip better symbolized this imperial shrinking of the world than Port Said, the place the Victoria stopped to refuel on that sunny afternoon.

Photograph of Port Said at sunset, 1894. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Most of the Arabs who fought each other for the chance to take the passengers from the Victoria ashore were not born in that city, because before 1859 Port Said did not exist. It had originally been built as a base for the construction of the Suez Canal, which was completed in 1869. Although the French originally controlled the canal, the British gained control over it, just as they gradually dominated the economy of Egypt. Finally, an invasion in 1882 made Egypt a British colony in all but name. All the things that Bly saw in Port Said—the gambling house, the shops, and the scores of impoverished Egyptians looking for work or charity from Bly and her fellow passengers—were there because of the construction of the Suez Canal and the influx of European traders and travelers that followed. Bly did not find Port Said very appealing, being struck by the misery and desperation that she saw in the seaside neighborhoods and crowded docks of the city, but it reflected the reality of the rapidly-changing world that encouraged her journey in the first place. Though night fell as Nellie Bly re-boarded the Victoria, the sun did not set on the British Empire.

Day 20 – Dec. 3, 1889: The Port of Aden

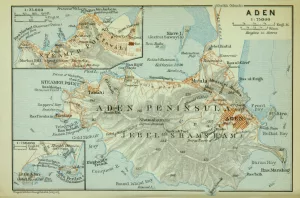

Map of Aden, 1914. The British port town where Nellie Bly came ashore is labeled as Steamer Point on the northwestern side of the peninsula, while the town of Aden proper is located on the western side. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

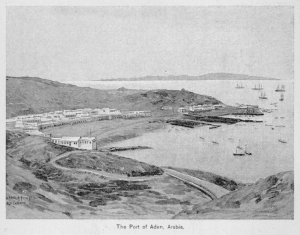

After traveling south along the Arabian coast for days, the steamship Victoria passed through the strait between Africa and Arabia, referred to in Arabic as Bab-el-Mandab (Gate of Tears). From there, it turned east towards the Yemeni port town of Aden. Although Nellie Bly saw many interesting places in the first few weeks of her journey, none of them seemed as unusual as Aden. She described the first thing she saw as a “large, bare mountain of wonderful height” rising from the sea. It seemed to be uninhabited, but the “mountain” was actually a dormant volcano with a town built in its crater. Although warned not to go ashore because of the intense heat, Bly decided to visit Aden “with a few of the more reckless” of her fellow passengers.

After the Victoria anchored in the bay of Aden, small boats filled with traders trying to sell their products surrounded the ship. Unlike the brand-new Port Said, Aden had been a center of trade for centuries. Its natural harbor and ideal location drew merchants from Arabia, Egypt, Persia, East Africa, and India. After the British conquered Aden in 1839, it became even more connected to the world’s markets. Bly noted the diversity that this trade brought. There were stores by the docks belonging to both Jews and Parsis. Parsis were an Indian ethnic group descended from followers of the Zoroastrian religion who migrated from Persia in the centuries after the Islamic conquest.

Along with these prosperous traders, the place Nellie Bly landed featured a British hotel, post office, and telegraph office. However, the actual town of Aden was located on the eastern side of the volcano. When she visited there, Bly discovered that the locals did not enjoy the same prosperity that the foreign merchants did, saying,

“When we drove into the town, which is composed of low adobe houses, our carriage was surrounded with beggars. We got out and walked through an unpaved street, looking at the dirty, uninviting shops and the dirty, uninviting people in and about them…Without buying anything we started to return to the ship.”

Native crewmen on a ship at Aden, 1894. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

When Bly and her companions returned to the Victoria, they were greeted by a group of Somali divers, some as young as eight years old. They showed off their skills by diving far underwater and retrieving pieces of silver in their mouths. Many of these men likely migrated to the Persian Gulf every year when pearl diving peaked from June to September to support the high demand in the markets of India and Europe. It was not a coincidence that they made Aden their winter home. British rule had turned Aden into the “gate to India,” key to trade and the defense of the empire. The coal depot there allowed steamships such as the Victoria to make it from Italy to India in a mere two weeks. Standing on the deck and looking at the Union Jack flying from the peak of the volcano, Bly reflected on the imperialism that made her journey possible:

“As I traveled on and realized more than ever before how the English have stolen almost all, if not all, desirable sea-ports, I felt an increased respect for the level-headedness of the English government, and I cease to marvel at the pride with which Englishmen view their flag floating in so many different climes and over so many different nationalities.”

Port of Aden, 1891. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Ships in Aden Harbor, 1890. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Day 25 – Dec. 8, 1889: Comfortable in Colombo

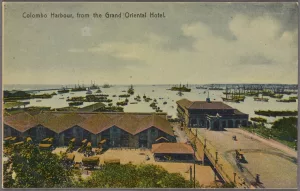

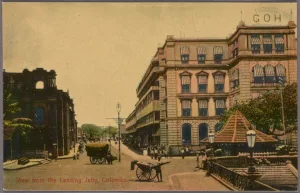

After almost a month of nonstop travel, Nellie Bly needed a break. Although her attempt to circle the world in 75 days normally prevented her from stopping, there were certain points in her itinerary where she had to pause in order to catch the fastest ship going in the right direction at the right time. One of these stops was at Colombo, the capital city of the British island colony of Ceylon (now known as Sri Lanka). Colombo, an old port town like Aden, had only been under British control since the 19th century. However, Colombo was almost as different from Aden as could be imagined.

View of Colombo Harbor from the Grand Oriental Hotel, c. 1910. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

As the Victoria floated in the harbor of Ceylon, Nellie Bly took in the rich blue of the coastal waters, the lush green of the rainforests, and, in the distance, the foggy mountains that filled the center of the island. Brought ashore in one of the narrow outrigger canoes prized by locals for their speed and reliability, she found herself equally impressed by the town of Colombo. The downtown area where Bly spent most of her time looked a lot like a European town. She described the buildings, mostly of British construction, as “artistic and picturesque.” The Grand Oriental Hotel where she stayed was an imposing four-story structure overlooking the harbor. She felt equally impressed when she took an evening drive past the beautiful Galle Face Hotel, the oldest and finest British hotel in Ceylon.

Nellie Bly fell in love with her surroundings and Colombo: the clean, well-maintained streets, the cool evening sea breezes, and the slow pace of life. She wrote of her daily routine:

After breakfast, which usually leaves nothing to be desired, guests rest in the corridor of the hotel; the men who have business matters to attend to look after them and return to the hotel not later than eleven. About the hour of noon everybody takes a rest, and after luncheon they take a nap. While they sleep the hottest part of the day passes, and at four they are again ready for a drive or a walk, from which they return after sunset in time to dress for dinner. After dinner there are pleasant little rides in jinrickshas or visits to the native theaters.

For 24 days, Bly had been so focused on where she was going that she had no time to really enjoy herself. Now, with her feet squarely on dry land, she could finally lean back in an easy chair on the hotel veranda, drink lime squashes and tea, and enjoy her visit as she waited for the ship that would carry her to her next destination.

View of the Grand Oriental Hotel from the harbor, c. 1910. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

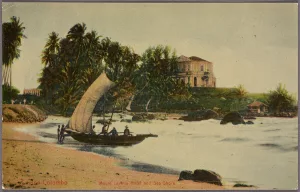

Mount Lavinia Hotel, several miles south of the port of Colombo, c. 1910. Nellie Bly came ashore in a boat like the one in the foreground. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

Galle Face Hotel, c. 1910. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

Day 28 – Dec. 11, 1889: Searching for Ceylon

Rickshaw drivers and passengers in Colombo, c. 1910. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

During Nellie Bly’s five-day stay on the island of Ceylon (Sri Lanka), she passed much of her time in the hotels and promenades of the British Colonial district of Colombo. However, she also ventured out to visit local sites and experience different cultures. One of her first exposures to local culture came at tiffin (an Indian English word for a midday meal such as lunch or tea) at the Grand Oriental Hotel. Nellie was impressed with the Sinhalese waiters. She noted their professionalism, fluent English, and their unique hairstyle, a so-called Psyche knot held in place by a tortoiseshell comb. Bly heartily enjoyed the food that they brought. She especially liked the curry, which was a mix of heavily spiced rice, meat, shrimp, and preserved fruit. It was served with a type of dried fish called Bombay duck. Bly later recounted a story that she had heard about this dish, writing,

The Shah of Persia was notified that some high official in India intended to send him a lot of very fine Bombay duck. The Shah was very much pleased and, in anticipation of their arrival, had some expensive ponds built to put the Bombay ducks in! Imagine his consternation when he received those ill-smelling, dried fish!

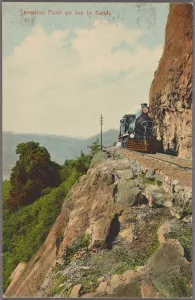

Cliffside tracks on the rail line that Nellie Bly took from Colombo to Kandy. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

In addition to this culinary adventure, Bly took in a dramatic show at a Parsi-owned theater and conversed in English with the Buddhist high priest at a college where men were trained to be monks. She became accustomed to the rickshaws that filled the neat streets of Colombo and came to appreciate the human-powered mode of transport, writing that it was “a great relief to have a horse whose tongue can protest.” Ultimately, though, there were only so many interesting things to see in Colombo, so Bly decided to go to the city of Kandy, which lay deep in the interior of Ceylon.

Sri Dalada Maligawa, or the Temple of the Tooth, c. 1905. This temple was constructed to house a holy relic, the tooth of the Buddha. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Unlike the coastal region, which had been under European control since the Portuguese came in the 16th century, the interior of Ceylon was independent until the British came. After they seized Dutch coastal possessions during the Napoleonic Wars, the British fought three bloody wars against the Kingdom of Kandy that gave them control over the whole island by 1818. This meant that the interior of the island largely lacked the colonial feel of Colombo and some of the other seaside ports. The change was noticeable as Bly took the winding railroad into the hills of Ceylon with several of her traveling companions from the Victoria. However, when she finally got to Kandy, she was disappointed. She had been told wonderful stories about the area, but she found it very hot and not particularly interesting. After visiting the Royal Botanical Gardens and a famous Buddhist temple, she returned with her companions to Colombo, sick from the heat. After she took a day off from touring it was time to leave. When Nellie Bly boarded the steamship Oriental to leave Colombo, it marked the end of a brief respite. With the clock still ticking on her 75-day goal and her competitor Elizabeth Bisland leaving Japan for Hong Kong, a single delay could cost Bly the race.

Day 33 – Dec. 16, 1889: At Penang

Wharf at George Town, c. 1910. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

ellie Bly enjoyed the second leg of her journey across the Indian Ocean more than the first. The Oriental was a smaller ship than the Victoria (the ship that had taken her from Italy to Ceylon), but she found the food much better, the quarters more comfortable, and the officers much kinder. It did not hurt that the weather was perfect. The winter monsoon season had passed, and Bly and her fellow passengers now spent their days on the deck in the sun. The weather was still beautiful when they reached the island of Penang, just off the Malay peninsula. But unlike her five-day stop at Colombo, Bly had only six hours to see the island.

Painting of the waterfall on Penang, 1818. Botanic gardens were built above this waterfall. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The main city of Penang, George Town, was unique in the region in that the British had built it from the ground up. Penang, or Prince of Wales Island, served as the first British base in the region. This meant that it became the largest British center of trade in the area in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. However, when Nellie Bly was ferried ashore there in 1889, Penang had long been surpassed by Singapore in importance. Even so, there were interesting colonial sites to be seen, such as the botanical gardens, which were located above a waterfall that Bly called “picturesque.”

Even though the settlement was colonial by its very nature, most people that lived there were not from Britain, and Bly noted, “English is spoken less in Penang than in any port I visited.” Instead, the people of Penang had come to participate in the commerce that flowed through the port. The population was mostly a blend of Malays (who were mostly Muslim), Indians (who were mostly Hindu), and Chinese (who followed various combinations of Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, and folk religions).

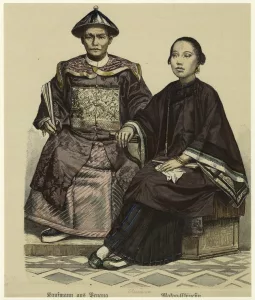

Drawing of a Chinese couple on Penang, 1848. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

As Bly had seen in Aden and Colombo, this diversity could be found throughout the Indian Ocean region. For millennia, Arabs, Indians, Somalis, Parsis, Chinese, Persians, and other groups crisscrossed the ocean, and British imperialism had only accelerated this motion. There were signs of this rich blend of cultures in every port. In George Town, Bly visited both a Hindu temple and what she called a “joss house,” which was a Chinese temple that might be used by several different religious sects. Priests from the temple invited her to drink tea with them, which she did until it was time to return to the Oriental.

When she got back to the docks, the weather had turned. The Oriental hurried to leave on time—so much so that dozens of laborers from a coal barge were nearly stranded on the ship as it began to head out to sea. The waters that Nellie Bly sailed in were defined by movement, and so she would move too.

Day 35 – Dec. 18, 1889: A New Companion

Singapore Club and Post Office, c. 1890. Bly wrote approvingly about the wide and even streets of Singapore. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

With the steamship Oriental anchored in the harbor off Singapore, Nellie Bly worried that her attempt to set a record might be in danger. A delay leaving Penang cost her crucial time in her goal to travel around the world in 75 days. To add to Nellie’s discomfort, the weather turned unbearably hot and humid as the Oriental passed between Malaya and Sumatra. Mirrors inside the ship fogged over from the high heat. Despite her worries, Nellie was relieved to come ashore at Singapore.

Cavenagh Bridge and the Government Offices, c. 1890. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

To explore the island, Bly rode in a kind of horse-drawn carriage called a gharry along a road “as smooth as a ball-room floor.” Singapore, like Colombo, had become one of the British Empire’s most prized possessions, and it was accordingly impressive. Bly ate dinner with one of her fellow passengers, a young Welsh doctor, at the stately Hotel de l’Europe. Other grand colonial structures that Bly probably saw were the Raffles Library and Museum, St. Andrew’s Cathedral, and Cavenagh Bridge, all built during Singapore’s rise to eclipse Penang as the foremost center of trade in Southeast Asia. Singapore, like Penang, had a great diversity of culture. People of Chinese descent formed a majority of the population, with large numbers of Malays and Indians as well. A sizable community of Europeans also lived in what Bly described as “beautiful bungalows” in the suburbs.

Hotel de l’Europe with St. Andrew’s Cathedral in the right background, c. 1880. In 1889, St. Andrew’s was the cathedral church of the Anglican Diocese of Labuan, Sarawak, and Singapore. It is now a Singaporean national monument. Courtesy of Leiden University Libraries.

Like all the other places she had visited, Nellie Bly was very interested in the local customs of Singapore. She recognized some practices, such as chewing the areca nut. Throughout South and Southeast Asia, the areca nut, also called betel nut after the leaf it is customarily wrapped in, has been enjoyed as a mild stimulant for thousands of years. However, in the 20th century the practice was found to have serious side effects, including an increased risk of cancer. At the time that Bly visited, people were unaware of the areca nut’s more dangerous properties. She did note, however, that the mouths of the people who chewed the nut were all stained red, saying “when they laugh one would suppose they had been drinking blood.” A less dangerous but equally foreign sight for Bly was the grand funeral procession that she watched with enthusiastic interest.

“First came a number of Chinamen carrying black and white satin flags which, being flourished energetically, cleared the road of vehicles and pedestrians. They were followed by musicians on Malay ponies, blowing fifes, striking cymbals, beating tom-toms, hammering gongs, and pounding long pieces of iron, with all their might and main. Men followed carrying on long poles roast pigs and Chinese lanterns, great and small, while in their rear came banner-bearers.”

Before returning Bly to the Oriental, her driver stopped by his home. While there, Bly saw a monkey in the doorway, and she instantly knew that she had to have it. When she re-boarded the ship, she brought along a new passenger. McGinty, as the monkey came to be called, traveled with Nellie Bly all the way home to New York.

Day 40 – Dec. 23, 1889: Hong Kong- The Crown Colony

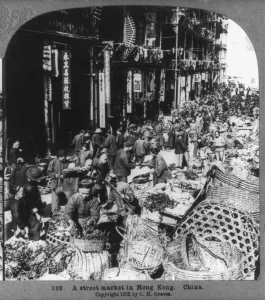

Street market in Hong Kong, 1902. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

As the Oriental sailed north from Singapore, the weather took a turn for the worse. Though Nellie Bly had not suffered from seasickness since her first days crossing the Atlantic on the Augusta Victoria, many of her fellow passengers were confined to their cabins as monsoon winds tossed the ship. Despite the storms and the delays, the Oriental arrived in Hong Kong two days ahead of schedule. Feeling confident that she was in reach of her 75-day goal, Bly made her way to the offices of the Oriental and Occidental Steamship Company to buy a ticket for her passage across the Pacific. When she reached the office, however, the salesman had bad news, informing Bly that she might lose her race. At first, Bly didn’t understand. The man told her that her competitor, Elizabeth Bisland, had left Hong Kong three days before, meaning that they had probably crossed paths somewhere in the South China Sea. Bisland seemed on track to make it home to the U.S. in 70 days, while Bly would have to wait in Hong Kong for almost a week. The news shocked Bly, especially since she hadn’t known that she was racing against Bisland. Nevertheless, there was nothing to do but try to enjoy Hong Kong.

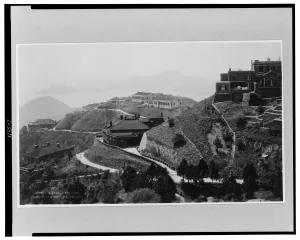

British rule began in Hong Kong in 1841 during the First Opium War. The British seized the island to serve as both a military outpost and a port free of the many restrictions that the Qing Empire placed on Chinese trade. The main British settlement became the city of Victoria, established on the northern side of the mountainous island. Bly wrote of Hong Kong,

“It is a terraced city, the terraces being formed by the castle-like, arcaded buildings perched tier after tier up the mountain’s verdant side. The regularity with which the houses are built in rows made me wildly fancy them a gigantic staircase, each stair made in imitation of castles.”

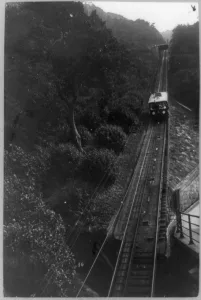

Tramway on Victoria Peak, c. 1900. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

As Bly travelled around the city in a sedan chair (a type of seat carried by two or more men using long poles on each side), the crowds of people amazed her. The narrow, sometimes winding streets sprawled up the mountain. Compared to Colombo and Singapore, Bly found Hong Kong to be thoroughly dirty, perhaps partially due to the densely packed population. The inhabitants were largely Chinese, but Bly also saw Europeans, Muslims from South and Southeast Asia, and Parsis.

One day, Bly decided to travel to the top of Victoria Peak, the mountain that dominated the center of Hong Kong Island. To get to the top of the mountain, she first rode the Peak Tram, a funicular railway only a year old when she visited. The Peak Tram, still in use today, is 4475 feet long and 1207 feet high, dwarfing Pittsburgh’s Duquesne Incline (800 feet long and 400 feet high). After reaching the upper station of the tramway, the summit could be reached on foot, or in Bly’s case, by sedan chair. Deeply impressed by the view of the city and bay below, Bly wrote, “After night the view from the peak is unsurpassed. One seems to be suspended between two heavens. Every one of the several thousand boats and sampans carries a light after dark. This, with the lights on the roads and in the houses, seems to be a sky more filled with stars than the one above.” Sights such as this one made the delay bearable. Nellie realized that she did not need to beat Elizabeth Bisland to New York to complete her mission, saying, “I am not racing. I promised to do the trip in seventy-five days, and I will do it.”

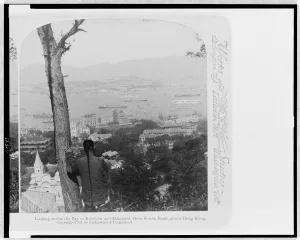

View of Kowloon Bay and the mainland beyond from Victoria Peak, 1900. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Estates on Victoria Peak, c. 1900. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Day 42 – Dec. 25, 1889: Christmas in Canton

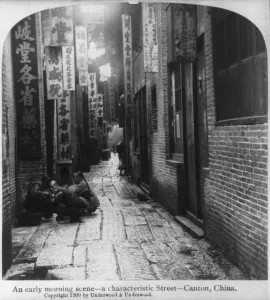

An early morning scene, Canton, China, c. 1900.

While Nellie Bly waited for her ship to leave for Japan, she sought out new experiences. When she felt like she had seen everything worth seeing in Hong Kong, Nellie decided to take an overnight ship to the city of Canton (Guangzhou), thinking it might give her more of a “pure Chinese” experience. In reality, though located in Chinese territory, Canton had become one of the largest centers of European activity in China, especially before the British seized Hong Kong.

When Bly arrived in Canton the next morning, her guide, a Chinese man educated at an American mission school, greeted her by cheerfully saying “A Merry Christmas!” Bly had forgotten that it was Christmas. She set off to tour, first visiting the island of Shamian, home to European and American commercial and government buildings. For the first time since leaving New York Nellie saw the Stars and Stripes flying over the American consulate. She could not help but be moved: “I felt I was a long ways off from my own dear land; it was Christmas day, and I had seen many different flags since last I gazed upon our own. The moment I saw it floating there in the soft, lazy breeze I took off my cap and said: ‘That is the most beautiful flag in the world, (and I am ready to whip anyone who says it isn’t.)’”

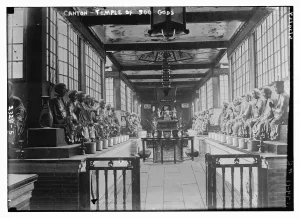

Bly’s tour of the city by sedan chair did nothing to ease her homesickness or raise her spirits. The city was crowded and dirty, and the places she visited were depressing. She traveled through narrow streets to the execution ground, where her guide told her about the punishments that criminals faced if they were caught; most were swiftly beheaded, but many met more elaborate and gruesome fates. After leaving the execution ground, she visited several temples (the city had hundreds), including the Hualin Temple (Temple of the Five Hundred Gods) and the Chenghuang Temple (called the Temple of Horrors by some European visitors, including Bly, for its graphic depictions of demons being punished). Bly became curious to see a famous leper colony outside of the city. Inside the village, there was such a strong smell that her guide advised everyone in their group to smoke to overpower the stench. The people afflicted with leprosy lived in grinding poverty, even worse than the population at large. Although some of them operated a small farm in the village, most were beggars. Bly came away feeling upset and more homesick than ever. Her guide led her and her companions into a temple to eat lunch. As she listened to faint, eerie, chanting from somewhere in the distance, someone mentioned that it was about midnight in New York. More than 8,000 miles from home, Nellie Bly ate her Christmas luncheon in the Temple of the Dead.

Canal separating the island of Shamian from the mainland, c. 1916. Shamian was divided into two concessions, a British one and a French one. Concessions, common in China in the late twentieth century, were legally the territory of the power they were leased to. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

Hualin Temple, c. 1910. Europeans called Hualin the Temple of the Five Hundred Gods because of its 500 statues of arhats, or people who are advanced along the path of enlightenment in Buddhism. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Day 50 – Jan. 2, 1890: The New Year Begins

Nellie Bly did not leave Hong Kong until the afternoon of December 28. The ship that took her to Yokohama, the RMS Oceanic, proved comfortable and its crew kind and skillful, to her delight. She got along well with her fellow passengers. When the clock struck midnight on New Years’ Eve, they sang “Auld Lang Syne” in unison. Bly wrote, “1889 was ended, and 1890 with its pleasures and pains began.” Meanwhile, thousands of miles away in Ceylon, Elizabeth Bisland slept in the Grand Oriental Hotel, preparing to leave the following day for Italy. The race around the world would come down to the next few weeks.

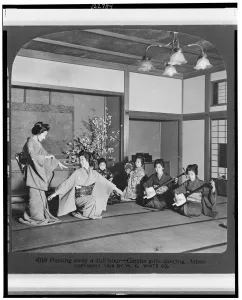

Geishas dancing and playing music, c. 1906. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

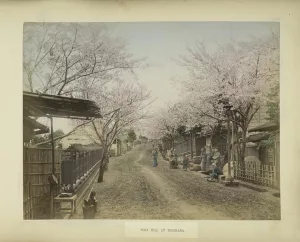

Unfortunately for Nellie Bly, she would have to spend the next week in Japan waiting for her ship to leave, waiting just as she had in Hong Kong. Fortunately, she was instantly charmed by Japan. The winter climate was pleasantly cool and sunny. In contrast to the dirty streets of China, she found Yokohama to have a “cleaned-up Sunday appearance.” She was just as impressed by the Japanese people. She described them as neat and dignified and remarked on their habit of holding their arms in baggy sleeves, joking, “On a cold day one would imagine the Japanese were a nation of armless people.”

One evening, Bly went with some of her companions from the Oceanic to a geisha house. The geishas’ grace and carefully styled hair and makeup impressed her. Although Nellie found the music jarring at first, she became enthralled by the dancing: “The musicians begin a long chanting strain, and these bits of beauty begin the dance. With a grace, simply enchanting, they twirl their little fans, sway their dainty bodies in a hundred different poses, each one more intoxicating than the other, all the while looking so childish and shy, with an innocent smile lurking about their lips, dimpling their soft cheeks, and their black eyes twinkling with the pleasure of the dance.” The geishas represented what Bly found so enchanting about Japan: the seemingly timeless sense of beauty and art that infused traditions, such as the celebration of the blossoming of the cherry trees. Japan was probably Bly’s favorite of all the places she visited. She later wrote, “If I loved and married, I would say to my mate: ‘Come, I know where Eden is,’ and…desert the land of my birth for Japan, the land of love–beauty–poetry–cleanliness.”

Cherry trees on Noga Hill in Yokahama, c. 1890. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

View of Mississippi Bay near Yokahama, c. 1895. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

Day 53 – Jan. 5, 1890: Japan: A Nation Transformed

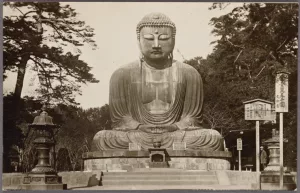

The longer she stayed in Japan, the more Nellie Bly experienced aspects of the culture that did not match with her first impressions of the country as quaint and “timeless.” On the one hand, she visited majestic structures such as the colossal statue of Buddha in the city of Kamakura, south of Yokohama. The statue, built in 1252, stands almost 45 feet tall and, according to Bly, is 98 feet in circumference at the waist. Bly took the opportunity to have her picture taken seated atop the statue’s thumb, itself more than two feet in circumference. When she visited Tokyo, Bly was able to see the grand castle that housed the imperial palace, rebuilt the previous year after a fire destroyed the old structure. However, just as the rich cultural heritage of Japan’s past was visible to Bly, so too did she witness its rapidly changing society.

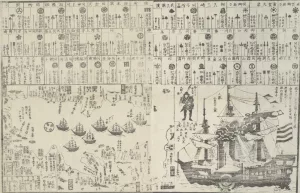

Japanese print depicting Commodore Matthew Perry’s 1853 expedition to “open” Japan, c. 1854. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Although Bly admired Japan’s past, she recognized that the country was undergoing a radical transformation; she believed that Japanese people “readily adopt any trade or habit that is an improvement upon their own.” It had not always been this way. When Commodore Matthew Perry arrived at the mouth of Tokyo Bay with a fleet of American warships in 1853 determined to open the country to American trade, Japanese technology and society were still rooted in tradition.

Having seen the growth of European imperialism in China and seeking to escape the same fate, some Japanese leaders sought the aggressive modernization of their country. In 1868, 21 years before Bly’s visit, the Tokugawa shogunate was overthrown and power became concentrated in the hands of the emperor and his ministers. The feudal lords (daimyos) were stripped of their lands, which became centralized under the emperor.

Nellie Bly noted that rapid advances in technology followed this political transformation. It revolutionized transportation: Tokyo had a streetcar line, bicycles were in use, and the country developed an extensive rail network. Electric street lights also became increasingly common. The adoption of Western movable type expanded the circulation of Japanese newspapers; Japan became one of the few places in the world, outside of the United States, where Bly received significant media attention during her journey. One Tokyo newspaper published the story of Bly’s meeting with Jules Verne and sent a reporter to interview her when she came to Japan. As Bly’s presence demonstrated, Japan had become a key stop on the steamer routes from America to Asia. In many ways, while Japan still retained its traditional culture, it was rapidly becoming part of the wider world.

Street scene in Tokyo, c. 1905. Notice the utility poles and the streetcars in the background. This photograph was taken over a decade after Bly’s visit to Japan, but it reflects many of her observations about technology and changing customs. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The Kamakura Buddha, or Kamakura Daibutsu, 1932. The statue, located on the grounds of a Buddhist temple called Kōtoku-in, is hollow and visitors can view its interior. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

Day 58 – Jan. 10, 1890: Life in Steerage

As Nellie Bly got closer to her destination, it became increasingly obvious how famous she had become in the United States. As she prepared to leave Yokohama, the band of the USS Omaha played a short concert in her honor. Aboard the Oceanic, she learned that the officers had written the following couplet all over the engine room:

“For Nellie Bly,

We’ll win or die.

January 20, 1890.”

RMS Oceanic, 1871. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Compared to the ships that Bly had taken before, the RMS Oceanic was relatively old, entering service in 1871. She was also slower, with a service speed of only about 14.5 knots (16.7 miles/hour) compared to the Augusta Victoria’s 19 knots (21.9 miles/hour). Nevertheless, the Oceanic was a sturdy vessel and Bly praised the quality of the food and service, writing, “in the Orient the Oceanic is the favorite ship, and people wait for months so as to travel on her.” Most passengers of the ship, however, did not share in the luxury that Bly enjoyed in first class. The Oceanic had room for 167 first-class passengers, while anywhere from 300 to 1000 passengers were crammed together in the lower decks, frequently called steerage.

Chinese passengers eating a meal on the steerage deck, 1901. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Third-class or steerage passengers sailed on every ship that Bly took, and yet they never featured in her accounts of her journey. However, her competitor Elizabeth Bisland did describe the conditions in steerage on the Oceanic. Like the Atlantic steamers, steerage consisted of one large room with many rows of bunks. full of migrants travelling to and from the United States. On Bly’s journey east, the vast majority of the passengers were Chinese migrants travelling to the United States seeking work. As Bisland saw travelling west, many of these people returned to China with the money that they earned. Some came back penniless. Others suffered from diseases such as tuberculosis and wished to be buried in their homeland. Bisland wrote, “It is common among the emigrants to America to fall sick…and to struggle back in this way to die at home. He seems afraid to breath (sic) or move, lest he should waste the failing oil or snuff out the dying flame ere he reaches his yearned-for home.” Amid the sickness and squalor, gambling games such as dominoes, chess, and fan-tan (a Chinese game like roulette) were all popular, as people did what they could to pass time in the miserable conditions.

Though surrounded on her journey by ordinary people seeking a better life, Nellie Bly never wrote about them. Noticed or not, however, the immigrants in steerage who came to the United States in search of opportunity helped to shape a nation.

Day 64 – Jan. 16, 1890: Racing Against Time

As Nellie Bly neared the West Coast of the United States and Elizabeth Bisland prepared to undertake the shorter Atlantic crossing, the race for New York had not been decided. Bisland’s journey had been just as interesting as Bly’s, forming a near mirror image. Although Bisland went west rather than east, she saw many of the same things. She crossed the Pacific on the Oceanic. Just as Japan had been Eden to Bly, it was the utopic land of Arcadia to Bisland. She summited Victoria Peak in Hong Kong, suffered in the equatorial heat in Singapore, enjoyed Christmas at sea off Sumatra, and watched a funeral procession on Penang. In Colombo, she stayed at the Grand Oriental Hotel and drove down the shore of Galle Face. She found Aden to be dry, alien, and timeless, musing that the people she passed looked as if they were “posing for Bible illustrations.” After sailing up the Red Sea and the Suez Canal, Bisland was unimpressed by Port Said, which she called a “wretched little place, dusty, dirty, and flaring with cheap vice.” After a short journey across the Mediterranean, she disembarked at Brindisi, which swarmed with passengers rearranging their travel plans because of a growing crisis: a global pandemic.

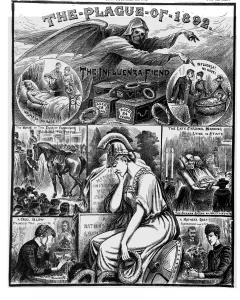

Illustration from Illustrated Police News depicting victims of the pandemic, 1892. Courtesy of the Wikimedia Commons.

The disease, eventually known as the Russian or Asiatic flu was first identified in May 1889 in the remote Central Asian city of Bukhara, in modern-day Uzbekistan. It spread slowly at first, but once it reached the Caspian Sea in the early fall it spread rapidly through Russia, reaching the capital, St. Petersburg, by the end of October. In December, it hit the rest of Europe and the east coast of the United States almost simultaneously. On December 29, a newspaper in Carson City, Nevada reflected grimly, “The influenza is coming around the world in a good deal faster time than Nellie Bly or her rival will make.” The disease had symptoms of fever, cough, headaches, fatigue, and in more serious cases pneumonia or heart failure. For most, a bout with the “Asiatic flu” was miserable but brief, but the virus could be deadly, especially in the elderly. An estimated one million people died worldwide by the end of the pandemic, which has generally been attributed to influenza, though recent science has suggested that a strain of coronavirus may have been responsible.

At the time, however, the pandemic was not a concern for Nellie Bly and Elizabeth Bisland. Neither traveler’s path was sure: winter snows jeopardized Bly’s rail crossing of America, and Bisland still did not know which port she would leave from to cross the Atlantic. Nevertheless, both were focused on the task that lay ahead. The pandemic that travelled with them became another reminder that the world was smaller than it had ever been – something each became determined to prove.

Day 70 – Jan. 22, 1890: Homeward Bound

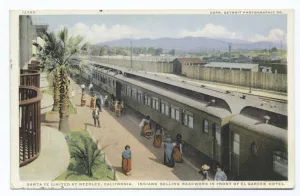

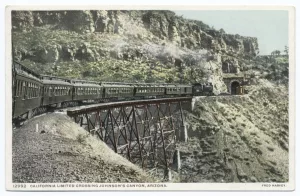

Train stopped at Needles, California, c. 1908. Nellie Bly’s special train passed through Needles at about 4:30 in the morning on January 22. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

As the steamship Oceanic came in sight of San Francisco early on the morning of January 21st, it seemed like the universe had conspired to prevent Nellie Bly from making it to New York in time to win her race around the world. The Oceanic had been rocked by storms for much of its Pacific crossing. The ship’s purser briefly thought that the ship’s bill of health was missing, which would have kept all passengers aboard the ship for two weeks. Rumors of smallpox aboard the ship circulated, but were proven false just hours before the Oceanic reached San Francisco. When a tugboat took Bly ashore at Oakland Harbor, she heard the news that most of the mountain passes were blocked by snow, meaning that she would need to detour through the deserts of the Southwest. Two editors the World sent to meet her found themselves trapped in the snow, although one crossed Emigrant Gap in the Sierra Nevada on snowshoes to make it in time to intercept Bly. Nearly everyone she met on her journey across the United States shared this dedication.

Train crossing Johnson Canyon, 50 miles west of Flagstaff, Arizona, c. 1908. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

Bly later wrote, “It seemed as if my greatest success was the personal interest of every one who greeted me.” Customs and railroad officials stayed up the whole night to ensure that she transferred trains in as little time as possible. She left Oakland in a privately chartered train that consisted of only one sleeping car and one engine. After climbing over the Diablo range, the little train raced southward past the farms and homesteads of California’s San Joaquin Valley. For months, Bly had travelled through countries where hardly anyone knew her name; it now seemed that everyone in America knew Nellie Bly. In every town, big or small, throngs of people stopped their work and came out in their best clothes to greet Nellie as her train whizzed through.

Lathrop, Modesto, Merced, Fresno, Bakersfield: the names flew by until they became meaningless. The train crossed the Mojave Desert by night and spent the next day traversing northern Arizona. Around 9:00 p.m., after passing through Gallup, New Mexico, the train crossed a bridge under repair that did not have its rails fastened. Nellie emerged unscathed. It seemed as if nothing could stop her from making it to New York in time to win the race. The San Francisco Daily Evening Bulletin published the following poem as an ode to her determination:

Poor Nellie Bly ne’er closed her eye,

She could not go to sleep,

She walked the deck, she heaved a sigh;

The sky was black, the waves were high;

The vessel seemed to creep.

She’d traveled many a weary mile,

Strange countries she had seen,

She had of curios many a pile,

A monkey with a ghastly smile

In a bird-cage painted green.

She fain would walk to Oakland pier

Her waiting train to catch,

For time was short and she’d a fear

Miss Lizzie Bisland might be near

New York, and win the match.

On entering port she heard, alack!

Her escort, far away,

On snowshoes broad, or on his back

Was slicing down the railroad track

To meet her on her way.

And Nellie heard of washouts dire,

Of storms that quickly came;

But while these stories raised her ire

She said with eyes that flashed with fire,

“I’ll get there just the same.”

Day 73 – Jan. 25, 1890: The Journey Completed

Chicago’s sixth city hall, 1908. This French Imperial-style civic building was constructed in 1885. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

As Nellie Bly’s special train roared east across the plains of Kansas on Thursday, January 23rd, she could hardly believe the reception that she received. Every station became a blur of excited faces, grasping hands, and adoring cheers. Telegrams arrived from around the country congratulating Bly on her seeming imminent success. Local leaders rushed to be the first to greet her. Bly believed that 10,000 people had come out to cheer her in Topeka; if this was true, around one third of the population of the city had stopped what they were doing and came to the train station to catch a glimpse of Nellie Bly.

The accolades continued the following morning in Chicago, where Bly’s train pulled in at about 8 o’clock. She was whisked downtown to the Chicago Press Club (across from City Hall on Clark Street), where she had a short reception with the gathered reporters. Riding a few blocks south to Adams Street, she ate breakfast at Kinsley’s, one of Chicago’s upscale restaurants. Before Bly left town, she stopped at the Chicago Board of Trade, where the shouts of frantic trading were suddenly replaced by wild applause when the brokers realized that Nellie Bly had arrived. With a brief wave of her cap, Bly was gone as quickly as she came, headed to Pennsylvania Station, and from there to Indiana and beyond.

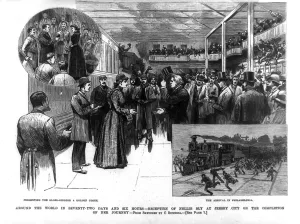

Woodcut of Nellie Bly’s reception at Jersey City, 1890. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The train that Bly now rode was an ordinary train, slower than the one she had boarded in California. Nevertheless, she made good time across the hills of Indiana and Ohio, crossing the Ohio River at Wheeling, West Virginia before entering Pennsylvania. She stayed up most of the night to greet a crowd of newspapermen at Union Station in her home city of Pittsburgh. Nellie only allowed herself to rest after the train left the “Smoky City” at around three in the morning. As a new day dawned, Bly’s train wound down from the ridges of the Appalachians, descending into Harrisburg, and then Lancaster by noon. At 1:25 in the afternoon, with anticipation building, Bly met a special welcoming party (which included her mother) in Philadelphia, less than 100 miles from her destination.

At 3:51 PM on January 25, 1890, the train carrying Nellie Bly pulled into the station in Jersey City, New Jersey, marking the end of Nellie Bly’s journey around the world. Completed in 72 days, 6 hours, and 11 minutes, it shattered the previous record for circumnavigation of the globe. Cannons were fired from the Battery the moment that Bly landed on the platform. The World reported that 15,000 people were at the station alone. The mayor of Jersey City gave a speech, but his words were nearly drowned out by the cheering throng. After only a few minutes, Bly crossed the Hudson River to Manhattan, where she went to the offices of The World in Park Row, and from there, north to her home uptown. In November of 1889, Nellie Bly embarked on a journey that she had been told she could never complete. Now 72 days and nearly 25,000 miles after setting out, she had succeeded—and was finally home.

Nellie Bly: A Postscript

Nellie Bly trading card, History Center Collection.

When Nellie Bly finished her journey around the world in January 1890, she did so as a newly minted celebrity. Her race against Elizabeth Bisland became one of the greatest press spectacles of the era. The New York World monetized her fame, holding contests, producing board games, and selling an “authorized biography.” Despite the profits that Bly’s journey provided for the owners and publishers of The World, she never received any bonus or salary increase. So shortly after returning, Bly left her position at the newspaper that had funded and publicized her journey.

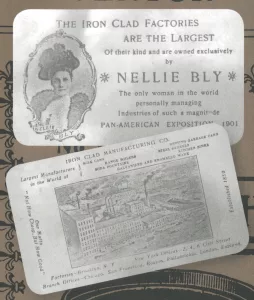

Yet another period of uncertainty in Bly’s life followed. She made money from a series of lecture tours and her account of her journey, but her financial situation remained unstable and she returned to journalism to support herself. In 1895, at the age of 31, she married a Robert Seaman, a wealthy 73-year-old industrialist. Though often unhappy in the marriage, Bly remained with Seaman until his death in 1904. By that time, she was running his business, Iron Clad Manufacturing Company. Over the following years, she registered patents for steel barrels and garbage cans of her own invention. The company did well for a time, but eventually fell into prolonged and bitter bankruptcy negotiations and lawsuits.

A business card advertising Bly’s Iron Clad Manufacturing Co. Courtesy American Oil & Gas Historical Society.

In 1914, as Bly was about to leave for Austria to look for funding to save the business, the First World War broke out and she quickly reentered journalism to fulfill a longtime dream of reporting from the warfront. She got her wish writing with horror about the tattered and filthy condition of the Austrian armies in Poland, Galicia, and Serbia. Bly became one of the most prominent advocates of the Austrian cause, raising American money for orphans and widows. Even after the United States declared war on Germany in April 1917 and on Austria-Hungary in December, Bly remained in Vienna as a favored guest until the end of the war. In 1920, Bly, a longtime supporter of the suffrage movement, lived to see the passage of the 19th amendment to the Constitution, which gave women the right to vote. On January 27, 1922, Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman, also known as Nellie Bly, died of bronchopneumonia at St. Mark’s Hospital in New York City, almost exactly 32 years after she finished her record-breaking journey around the world.

Ultimately, Nellie Bly’s circumnavigation record only stood for a matter of months. Eccentric businessman George Francis Train traveled around the world in just 67 days, starting and ending in Tacoma, Washington. By 1913, John Henry Mears had slashed Bly’s record in half, completing the journey in under 36 days. Today, the trip can be completed by airplane in less than 36 hours, and the International Space Station takes only 90 minutes to completely orbit Earth. Nellie Bly was neither the first nor the fastest to travel around the world, and yet she remains an enduring source of fascination to the present day. The most likely reason for this is Nellie herself. Her sharp wit, courage, and sincerity shine through in her writing and the writing of those that knew her. Nellie Bly, a journalist, traveler, industrialist, inventor, and philanthropist, left a mark on Western Pennsylvanian and American history that has stretched far beyond the day when she stepped off that train in Jersey City 131 years ago.

Nellie Bly seated, c. 1922. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Bly talking to an Austrian officer in Poland, 1914. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Visit the Museum Shop