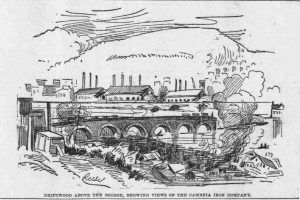

The Great Johnstown Flood of 1889 attracted many ambitious correspondents who hoped to be the first to document the catastrophe. Pittsburgh-based muckraker Cara Godwin Reese arrived at the site alongside her brother, Charles. At the time of the flood, Cara had already made a name for herself within the journalism field because of her segment “Cara’s Column” featured in the Commercial Gazette. Her notes and sketches of the devastation appeared in the Pittsburg Dispatch a few days following the flood on June 2 with the headline “WIPED OUT BY WATER. Johnstown the Pretty Mountain City, Swept From the Surface of the Earth.”

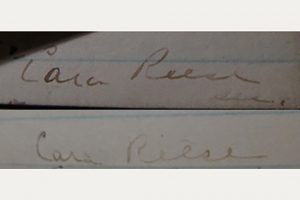

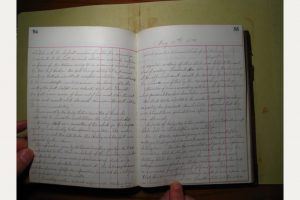

Charles Reese was a famous illustrator whose work had been published in Pittsburgh, New York, Philadelphia, and Boston newspapers. Because Charles’s sketches of the flood also appeared in the Pittsburgh Dispatch, for over 100 years most historians assumed that Cara’s illustrations of the flood were also the work of Charles. However, research conducted by Rose Klaiber, under Professor Timothy Bintrim of Saint Francis University, confirmed that it was Cara’s sketches featured in the Pittsburgh Dispatch – not her brother’s. Klaiber came to this reasoning by analyzing meeting notes from the Women’s Press Club, specifically by comparing the signature appearing in the notebook to the one on the paper.

It was not uncommon for men to receive credit for the work of women. What was uncommon, though, was the involvement of female journalists in environments that were considered “unsafe” for women. It would have been highly improper for Reese to travel to disaster zones, especially while wearing a long, multi-layered skirt that would have hindered her ability to properly navigate the high water and muddy terrain. Her rebellious participation in reporting tragedies by visiting unsafe locations that were deemed unsuitable for women to inspect was not admired during her career. In fact, the executive committee of the Women’s Club of Pittsburgh had made attempts to expel her from the organization in an attempt to prevent her from putting herself in harm’s way for the sake of journalism. Her colleagues, including Elizabeth Wilkinson Wade (“Bessie Bramble”) defended Reese, insisting that women had a place in reporting dangerous environments as it may reach audiences that their male counterparts could not.

Cara Reese’s successful career, from maintaining her own column to seeking out opportunities and reporting on unsafe conditions, was pivotal in inspiring other muckrakers to do the same. However, Reese differed from other female journalists during this period because she used her real name while most women who reported utilized pseudonyms to conceal their true identity. Their reasoning for doing this was to prevent similar stresses to what Cara faced while reporting. Women lost their place in society for being writers because the occupation frequently involved critiquing an individual, idea, or organization. Pseudonyms gave these female journalists the protection from being ostracized.

Willa Cather, for instance, used fifteen different pseudonyms throughout her writing career. Depending on which Pittsburgh periodical you picked up, her pen name could be Sibert (her middle name), Mary K. Hawley, Helen Delay (“Hell’n Delay”), John Charles Esten, Henry Nickelmann, John Charles Austen, George Overing, Elizabeth L. Seymour, Emily Vantell, Gilberta S. Whittle, Lawrence Brenton, and Leslie Helmer. The late nineteenth century saw the rise of the budding home and fireside magazine, The Home Monthly. Due to its competition being the Ladies Home Journal, contributors were scarce. Because of this, Cather wrote most of the first issue under a variety of pseudonyms. Evidently, pseudonyms weren’t just used to hide women’s identity, but a tool that permitted them to publish more without their name being overused. If it was overused, perhaps they worried the content would hold less weight. In the event that the journalist covered a controversial issue, amassing wide debate, the recurrent use of her name may have deterred readers from continuing to read her work. Pseudonyms ultimately permitted ambiguity and flexibility in her writing.

Described as a “force to be reckoned with in Pittsburgh,” Elizabeth Wilkinson Wade or “Bessie Bramble” was known for her spirited works centered around feminist topics, notably the wages of working women, domestic abuse, and organizations that supported the patriarchy. According to Patricia Lowry of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, it would have been unfeasible to cover such weighted topics without the cover of a pen name. Wade’s pseudonym was developed by combining the name of her daughter with a shrub. Bessie Bramble concealed Wade’s identity for many years, allowing her to express opinions with anonymity towards influential figures within the community.

Adelaide Mellier Nevin (d. 1895) was responsible for creating Pittsburgh’s first society column, using the pen name “Miss Nothing.” She later abandoned her cover, writing The Social Mirror in her own name, indicating that the content matter was likely becoming more accepted by the public.

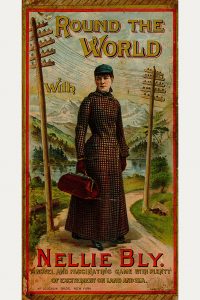

Perhaps one of the most well-known female journalists of this period who took a pseudonym was Elizabeth Jane Cochran, or “Nellie Bly” (d. 1922). After writing a heated, yet well-written letter to George Madden, the editor of the Pittsburg Dispatch in 1885, Bly was offered a career. Madden, aware of the implications that could arise from a woman using her given name, asked the printers to use the pseudonym Nellie Bly, after Stephen Foster’s folk song. Under the cover of the nom de plume, Bly began writing on women’s issues, exposing local Pittsburgh businesses that maintained harmful working conditions. Like Reese, Cochran traveled to dark and dangerous places unescorted, searching for stories that needed to be illuminated.

Other reputable female journalists writing under pseudonyms throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries were commonly members of the Women’s Press Club, a literary and professional organization for women in the news media. Mary Temple Bayard was a witty writer known as Meg. Mrs. H.K. Wallace wrote under the name of Aunt Patience for the Pittsburg Press. Mrs. Dallas Albert of Latrobe utilized the pseudonym Ellice Serena while writing weekly feminist columns for the Pittsburgh Dispatch. Getrude Gordon, or Gertrude B Kelley, was also among these women.

Today female photographers, broadcasters, writers, journalists, editors, and women who work in similar spaces no longer have the need to use false names to protect their identity. That these women are comfortable enough to use their real names speaks for the progression of the feminist movement, specifically how they now have the courage and ability to report freely, truthfully, and ambitiously.

The stories of these courageous female journalists can be found in our exhibition, A Woman’s Place: How Women Shaped Pittsburgh, open through Oct. 6, 2024.

About the Author

Rae Tunstall was a curatorial intern at the Heinz History Center whose research focused on women’s history.